School’s Out

Massachusetts Youth in Adult Correctional Systems Denied Education

August 2022

Educating incarcerated youth benefits society in multiple ways and is not only legally mandated but is the right thing to do from a moral, fiscal, and community safety perspective. This report provides a comparative overview of educational approaches and outcomes in the adult and juvenile systems for incarcerated young people aged 18–21 in Massachusetts, with a focus on special education. The report was compiled with data from a series of public records requests, policy and practice reviews, and key informant interviews.

Key Findings

Accountability for providing educational services to young people incarcerated in county Houses of Correction (HOCs) and state Department of Correction (DOC) facilities is inadequate.

One primary challenge is that no single agency takes ultimate responsibility to ensure that incarcerated 18- to 21-year-olds with disabilities receive education to which they are entitled. The agency that is obliged under law to assure the delivery of special education services in jails and prisons, the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), has largely delegated the duty to local districts that typically do not act unless the child and/or parent hires an attorney.

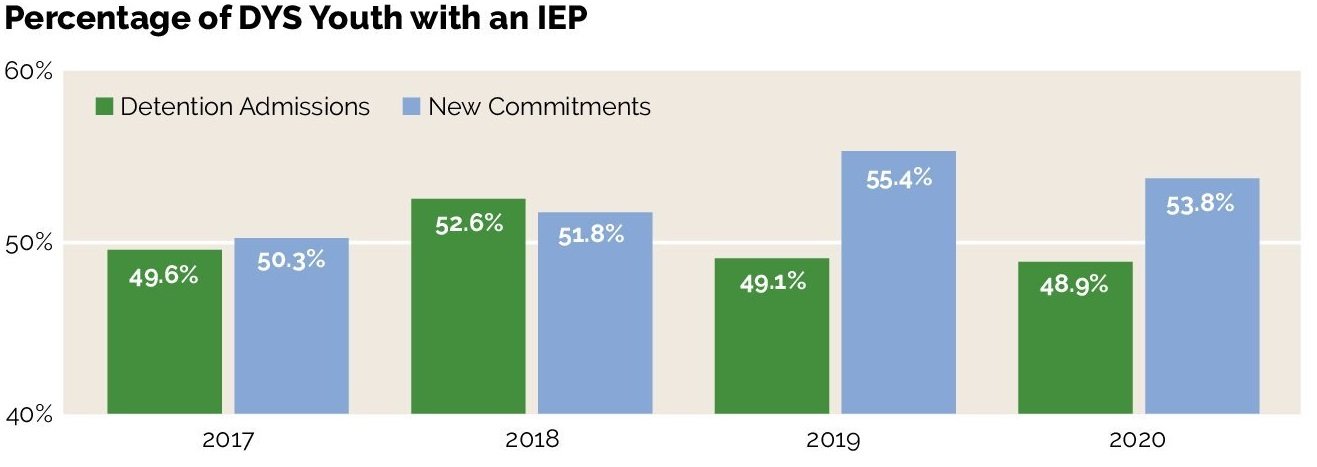

HOCs and DOC under-identify young people with existing Individualized Education Programs (IEPs).

HOCs are tasked with identifying youth in their care who have an IEP and therefore qualify for special education services. Based on data received from DESE, DOC, and HOCs that reasonably complied with public records requests, we estimate that HOCs under-identified between 142 and 189 youth who had IEPs in place each fiscal year between 2018-2020.

The Massachusetts DOC significantly under-identifies incarcerated students who have existing IEPs. While 346 incarcerated persons age 18–21 were enrolled in school at some point over the last four years, “DOC records reflect that of the inmates age 18-22, only one housed at MCI–Norfolk and one housed at MCI–Framingham were identified as needing and receiving special education services during the last 2 1⁄2 years.” Two out of 346 represents only 0.5% of the population of school-aged young people, which must be a huge under-identification of youth with special education needs. DOC likely failed to provide FAPE to 176 youth with disabilities in its custody between 2018 and 2020.

The state Department of Youth Services (DYS) meets more of its legal obligation to provide educational services for children and young adults in its care than do HOCs and DOC.

The enhanced educational access and experience at DYS stems from differences in system orientation in the juvenile system as reflected in the law, regulation/practice, and organizational culture, as well as dedication of staffing and resources to educational programming as part of a Positive Youth Development model. A data sharing mechanism exists between DESE and DYS to identify IEP eligible students in DYS custody.

Recommendations to provide better educational services for incarcerated youth

Recommendation 1

The Massachusetts Legislature should raise the age of juvenile jurisdiction to include 18- to 20-year-olds in the Juvenile Court system, because youth in DYS custody are more likely to access their educational rights and receive developmentally appropriate treatment.

Recommendation 2

DESE, HOCs, and DOC should improve interagency data sharing to improve identification of incarcerated youth with IEPs already in place.

Recommendation 3

HOCs and DOC should create a dedicated education budget and prioritize educational programming to ensure all school aged youth (up to their 22nd birthday) have access to school every weekday and incentivize educational participation through good time credit.

Recommendation 4

The Office of the State Auditor should consider investigating educational obligations and practices for school-aged youth (18 to 21) at HOCs and DOC in the spirit of increasing accountability for legal obligations.